“Prior to coming to live in Wonthaggi I lived in Fitzroy in an old warehouse. It only had three brick walls to it as it shared a common wall in the form of a huge cool room with its neighbour which was a converted small goods factory. Prior to purchasing it I was an Industrial Relations Manager with Ansett and used to meet with trade union officials in the offices of the Liquor Trades Union across the road. I used to look down on it as I was berated by a looming six foot three trade union boss and think that at least I wasn’t getting as much a hard time as the pigs that were being turned into salamis just a few yards away.”

“Prior to coming to live in Wonthaggi I lived in Fitzroy in an old warehouse. It only had three brick walls to it as it shared a common wall in the form of a huge cool room with its neighbour which was a converted small goods factory. Prior to purchasing it I was an Industrial Relations Manager with Ansett and used to meet with trade union officials in the offices of the Liquor Trades Union across the road. I used to look down on it as I was berated by a looming six foot three trade union boss and think that at least I wasn’t getting as much a hard time as the pigs that were being turned into salamis just a few yards away.”

That was over 20 years ago and Fitzroy was on its way to becoming the eclectic mix of coffee shops, eateries and funky stores that it is today. Step back even further to the mid-1960s and the only whiff of coffee would be emanating from the houses of the many immigrants who had settled in the area. Slums were being demolished and in their place high rise apartment blocks erected. Families who had happily played cricket in the laneways of Fitzroy were forcibly evicted and their 100 year old homes demolished to make way for the ‘future’.

Chris Lermanis ventured into this landscape to record the scenes as a young man in his early twenties. It was quite a culture shock for Chris who was living in Brighton and who almost felt like a tourist as he took his photographs with his trusty Pentax camera. In those days of course there was no such thing as auto focus lenses or in built light metres. Everything had to be done from scratch – and quickly if he was able to capture the moment. And then into his dark room to develop the precious negatives.

Chris was born in Latvia in 1941 in the week that Hitler invaded Russia. His father did not see his son grow up as being a Latvian border guard he was not viewed favourably by the Russians and after a failed attempt to flee to Sweden ended up in the notorious Gulag. He was sentenced to 15 years forced labour. In 1943, Chris and his mother were being gathered up by the Germans along with thousands of others as the Russians fought back and ended up in a displaced persons camp which was to be their life for the next six years.

Chris and his mother migrated to Australia in the wave of the post war immigration boom and settled in the infamous Bonegilla Migrant Centre. Living in unlined timber-framed buildings with corrugated iron walls was not idyllic particularly in the heat of summer. Bonegilla was inadequately staffed and its ill-equipped hospital resulted in 13 newly arrived children dying from malnutrition. Over the years there were protests about food and conditions and posted signs declared “Bonegilla camp without hope”.

The family moved to Melbourne and after finishing high school Chris pondered which occupation he would settle in to. After 6 months of a merchandising cadetship with Myer Chris realised there would be no excitement for him in the sale of shoes or umbrellas and ended up as a primary school teacher. Interestingly in the early 60s primary school teaching was a serious male occupation unlike today where males account for less than 20% of the staff.

Whilst Chris and his mother tended to keep to themselves there was still contact with Latvian friends and relatives. In 1971 an adventurous Chris travelled to Latvia to meet his father. “It was emotionally harrowing and we even looked alike.” His father had remarried and warmly received his son, but spoke sparingly of his time in the Gulag. His father has since passed away, but lived to age 93 despite his deprivations. Chris thinks he is of good genetic material. He is thankful for his heritage of being born in a small and proud nation with a strong culture. But he did find the food of potatoes, cabbage and herring a little monotonous.

Chris loved teaching, but did not like the constant curriculum changes and departmental edicts. When Jeff Kennett’s government determined the closing of many schools Chris took the opportunity of a redundancy package. At the time he was living in Belgrave but he was never comfortable there over summertime. He remembered all too well that it was only by chance that his house had been saved in the Ash Wednesday fires of 1983 when he lived in Cockatoo. Each summer in Belgrave he and his wife lived in fear that their home would be destroyed and kept boxes by the door, ready to go.

In the end they decided to search for a place by the sea, away from the bush, and found their ideal in Woolamai.

In retirement Chris has found plenty of time to pursue his passion of photography. He takes himself away and above all is interested in capturing images that have something to say. He often travels to the Flinders Ranges where he takes photographs of what he thinks of as the essence of Australia – abandoned farmhouses with roofs, tanks and fences mostly of corrugated iron. Chris has still not succumbed to the temptations of digital technology – and steadfastly continues to enter into his darkroom to create his images.

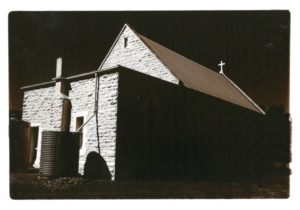

His Holy Water series, which are a part of a larger theme of water in a dry land (some of which will be shown at the ASPI Easter Exhibition in Cowes), is a collection of photographs of outback churches with attached corrugated iron water tanks.

A collection, and on show at ArtSpace from the 27th of March, is a series of photographs of the outback silos standing 30 metres high and covered with spectacular murals. In order to create a photograph different to those developed by the many tourists that visit the silos, Chris has been back in the darkroom trialing an interesting technique – lith printing – which softens highlights and hardens shadows. “It is a slow process and each of the prints are a one off. Sure anyone can take a photograph but it is the story and where the image takes you that is important.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.